- Home

- Maureen Daly

Seventeenth Summer Page 4

Seventeenth Summer Read online

Page 4

Even when you say prayers for it, a thing almost never happens the way this did. In five minutes more we would have been halfway down the block and I’d never have heard the phone ring at all. It was just as if it had been planned. Kitty and my other two sisters were already on the front steps with their hair all brushed and ready to go to the movie, and I had just run back upstairs for a clean handkerchief for my mother when the phone rang. It was Jack calling.

He knew it was late he said, and he would have called earlier, but his father hadn’t decided to let him use the car until a few minutes ago and would I like to go out for a while? Probably drive to Pete’s or something….

“Of course not,” my mother said firmly. “Tell him that you were just going to the movies with us. The idea of thinking that you can go out any night in the week! Does he think you have nothing else to do?”

“Oh, let her go, Mom. With school just out it’s good to fool around.”

“Sure. It’s a wonderful night to go out and Pete’s is on the lake—let her go, Mom. The show isn’t very good anyway.”

“It won’t hurt, Mom. Let her go.”

My sisters were talking. I said nothing.

She mused a moment. “Well, all right. You may go this time but don’t let this boy”—she knew his name was Jack—“think that you can be running around all the time. You have better things to do. I thought this was the summer you were going to get so much reading done. But you may go this time.”

Halfway down the front sidewalk she turned and called, “Angie, you’d better put on your blue linen.You don’t look very dressed up for an evening.”

And I hurried upstairs to get ready, trying to calm the crowded, fluttery thoughts in my head. “I’ll see you in ten minutes then,” Jack had said.

You would like Pete’s, I know. There is no other place quite like it. When we were little we used to go for drives on warm summer evenings with my mother and father and stop there for ice-cream cones. Everyone did. And now that the children were grown up they still stopped—to dance now and have Cokes or beer instead of ice-cream cones. Mr. Mingle (everyone calls him Pete) is past eighty and can just barely shuffle around, but he remembers everyone and can call each by his own name. The building, old and square, is built right on the lake shore about three miles out of town and the inside hasn’t been painted for years. Outside, the lawns and flower beds have all run into one and stretch to the water’s edge in a tangle of weeds. On one side is a gravel parking lot, for Pete’s is always jammed at night with the crowd from high school.

We went in the side door, Jack and I, and sat in one of the booths which are set back in latticework arches with little black painted tables, the tops rough with carved initials. The edges of the carving are worn smooth by hundreds of Coke bottles and glasses of beer and by hands that have held each other tight across those tables. Off in one corner is Pete’s old and irritable parrot perched on a wicker stand, scrawking at anyone who comes too near, continually rolling its yellow eyes in anger, and pecking at the pumpkin seeds in its food dish with an ugly beak that is chipped in layers like an old fingernail.

I felt a little scared. It was almost like making my debut or something. I had never been out to Pete’s on a date before, and in our town that is the crucial test. Everyone is there and everyone sees you. I knew of a girl once who went out to Pete’s with her cousin and no one else asked her to dance or paid any attention to her, and so she went away to college in the fall and never had dates at home for any of the dances at Christmas or Easter. If you don’t make the grade at Pete’s, you just don’t make it.

“What will you have, Angie?” Jack asked. He hadn’t said much to me on the way out—not much about me, I mean. Halfway to Pete’s he had asked if I heard anything funny in the motor of the car—like a faint knocking or something, so we drove almost two miles in silence, he with his head cocked to one side and a scowl on his face and I sitting very still trying to look as if I were listening hard. In the end, just as we got to Pete’s, he decided it had been his imagination after all. So you see, when he said, “What will you have, Angie?” that’s when my evening, the evening of my “coming out,” really began.

At Pete’s you choose from only four things—beer, root beer, Coke, and peanuts salted in the shell. No one ever wants anything else. I wanted a Coke and he wanted a glass of beer and we both wanted peanuts, so Jack went up to the bar to get them to save old Pete the trouble. The bar is in a smaller room in the front and the jukebox is there, too, and that’s where all the boys who haven’t dates sit and play cards and watch the other fellows and girls as they come in.

While he was gone I traced through the maze of initials on the table top, trying to make out someone’s I knew. Maybe, I thought, his is here somewhere. There was a heart with a J and another letter in it, but the second initial had been carved over so I couldn’t make it out. I thought of scratching my own A. M. in a small, smooth space—just so it would look as if I had been there before, as if someone had wanted to carve my initials like they did other girls’—but I couldn’t find anything to do it with. If I took a hairpin out of my hair the curl on top would fall down and I would have to fix it all over again.

I took the little mirror out of my purse to look at myself—I didn’t often wear my hair with that big curl on top, and because they had all gone to the movies there was no one at home to consult before I left. It looked all right to me, but then Pete’s is so hazy-dark that everything looks different anyway.

Swede walked in from the bar just then with a glass of beer in his hand and slid into the booth across from me. “Hi-yah, Angie,” he said. “Jack will be back in a minute. He’s talking to some of the fellows.” He paused to take a sip of his beer. “Well, what’s the good word?”

I didn’t know just what he meant by that so I smiled, telling him I hadn’t known he was going to be out here, and we began to talk about little things—did I drink beer, and whether or not the kids would like Pete’s as well if it was all fixed up, and how come a good girl like me had wasted my talents by not going up to high school? I liked Swede. His hair was blond and kinky and he looked so well-fed and healthy that it seemed as if his chest would burst right through his sweater. Besides, he made me feel like a pretty girl, talking as he did—“A good girl like me wasting my talents by not going up to high school.” Maybe it wouldn’t be so hard to talk to the other fellows after all.

When Jack came back with my Coke and peanuts he brought two of his friends, boys who had played basketball with him, and in the beginning I felt quite at ease with them. After the introductions they didn’t pay much attention to me, but just talked about school, and that they had heard “Old Baldy” wasn’t going to be teaching Math next year after the way he had thrown that book at Chuck Wilkins that day, and who was the new girl from Ninth Street that Dick Fox had had out for the past three nights? I just listened and laughed and drank my Coke and didn’t seem to be out of place in the least. I’m sure none of them thought that this was my first night out at Pete’s on a date and that I’d never sat in a booth with four boys at once before. I tried to act very natural and casual and didn’t say much.

I didn’t know Jane Rady was there that night at all until she came over from one of the darker booths near the back to talk with us, saying, “Well, Angie Morrow, I didn’t know you were here!” In a funny surprised sort of voice that really sounded as if she were saying, “Well, Angie Morrow, I really never thought I’d see you out on a date!”

Jane is much shorter than I am with fluffy blond hair that she lets hang loose with no hairpins or bow or anything. And for some reason when you look at Jane you always see her mouth before you see the rest of her face.

All four of the boys said, “Hi, there, Janie!” and one stood up to give her his place but she said, “Oh, don’t bother, I’ll just squeeze in.” It was so crowded that Jack had to put his arm around the back of the booth to make room and she looked at him with a little smile and purred under her

breath, “Uum, nice!” and everyone laughed and said, “What a girl, Janie!” and I laughed, too, but my face felt stiff and the laugh came out funny though I don’t think anyone noticed it for they were all listening to her.

I sat and listened too. It wasn’t because I hadn’t gone up to high school then; Jane hadn’t gone up there either but she knew the things to say. She knew what they were talking about when they said, “Remember the night after the Sheboygan game when there were seven of us coming home in the back seat?” and “Did you hear what happened to Bartie when he broke the drum at the graduation dance last week?” Jane did remember and she had heard and she added a few more things that made the boys laugh and look at each other and then back at her. And of course, I laughed too but I felt very uncomfortable and conspicuous; and though I drank my Coke in little sips it did not last long enough, and I had to sit sliding ice round and round in the empty glass and rack my brains for something to say, something that would make them remember that I was there or make them at least think that I thought what they were talking about was interesting too.

I thought of saying brightly, as if the thought had just come to me, “Did Jack and Swede and I ever have fun sailboating last night!” But they might all turn and look at me, saying with a questioning inflection, “Yeah?” and I wouldn’t know how to go on from there. Maybe Jack wouldn’t want them to know we had been sailboating—after all he hadn’t mentioned it himself, had he? He was lighting a cigarette for Jane just then and she blew the smoke in his face in a playful puff as she said, “Thanks,” and smiled a little half-smile with the side of her mouth that didn’t have the cigarette in it.

Through my mind mulled all the things she used to tell me about Jack when she sat next to me in the history class. The evening dragged on and on. The Coke had left a sweetish, sickening taste in my mouth and my whole body ached with wretchedness.

Swede’s beer glass was empty and he stood up saying, “Can I get anything for anybody?” and balancing the empty glasses in a pyramid, he went out to the bar. In the other room someone had put a nickel in the jukebox and music began to come through the round amplifier all hung with crepe paper above the door. Jane gave a little gasp and made her eyes and mouth very round. “Oh, that song—I love it! Jack, dance with me!” She stood up, holding out her hand.

Jack looked at me and said, “’Scuse me, will you?” I didn’t blame him. Anyone with a date as dull as I was would naturally want to dance with someone else. Out of the corner of my eye I watched him. I didn’t care, I said to myself. I was all wrong about last night anyway. It didn’t make any difference—he was just like any other boy, any boy at all. I was all wrong.

The music seemed to fill the whole room at Pete’s with its poignant tilt, and the little liquid waves of music seemed to curl in and out the latticework that arched the booths. I sat staring at the table and slid my Coke glass so that it covered the carved heart with the initial J in it. Of course I was all wrong about last night.

There were other people dancing now but it didn’t seem to matter; Jack and Jane weren’t looking at anyone. She was much shorter than he and danced with her arm crooked around his neck and her head back so that her fluffy hair hung halfway down her back. Neither of them seemed to be saying anything just dancing and letting the music float round them. I tried to keep from watching them too hard. One of the fellows in our booth became restless and muttering,” ’Scuse me,” went out to the bar. I don’t care, I thought. Let him go. I know I’m dull. I don’t care if he wants to go—everyone can’t be like Jane Rady. It seemed as if my whole face was stiff with scowling and my eyebrows must be growing straight across my nose, dark and heavy.

The full disappointment of the evening struck me all in a lump. It was the rollicking sadness of the music that made my heart feel sore. It was that and the thought of last night and all the silly, wonderful things I had been feeling all day and the way my heart had jumped when the phone rang and it was Jack. And it was because he was there now dancing with Jane Rady when he hadn’t even danced with me once and I was his date. And the other fellows didn’t like me either and I was awkward and didn’t know anything to talk about. It was all that and the sudden, sickening realization that I couldn’t fool myself. I did care! It wasn’t because it was the first boy I had ever really been out with—this was something different. I had never felt this way before—and he didn’t even care! Someone had put another nickel in the music box and they kept on dancing.

So I just waited, toying with my empty glass, and the corners of my mouth seemed suddenly tired and a peculiar lonesome ache went through me right down into my hands. I just sat, not thinking of anything in particular, feeling as useless, as emptied, and as hollowed as a sucked orange.

Lying in bed that night thinking it over, slowly and dearly, I decided it was me that was all wrong. Other girls knew what to do. Other girls could talk with fellows and laugh with them and say funny things. Jane Rady could do it. Jane knew how to dance with her head back so her hair fell long and smooth as silk thread. Mine was curly all over and no matter how much I brushed it there were always little wispy curls around my face, as if I had just come out of a steamy shower. I wasn’t the kind of a girl who could ever go into McKnight’s drugstore and have a crowd of boys come over to sit with me, wanting to buy me a Coke. And I know I’d look silly if I shook my finger as if I were trucking and clicked time with my tongue, swaying from side to side the way some girls can do, when good dance music came on the radio. None of the fellows at Pete’s had even offered me a cigarette because they could tell just by looking at me that I was the kind of girl who wouldn’t know how to smoke!

And of course I had acted all wrong too. It made me squirm inside to think of it. When Jack and Jane had finished dancing I should have smiled as if I hadn’t cared at all and said something smart like “smooth stuff there,” or “just like Veloz and Yolanda,” as any other girl would have done. But I didn’t. My face had been stiff with misery, and seeing everyone else laughing and having so much fun I couldn’t help thinking how much better it would have been if I had just gone to the movies with my mother and sisters. You know, if you don’t see all the fellows and girls out on dates you don’t think about it and then you don’t feel so unhappy. If I hadn’t gone out to Pete’s at all things could have gone on as they had before—“Angie Morrow doesn’t go out on dates because her mother doesn’t let her”—and no one would have known I was such a drip. But now even Jack knew.

Only once during the whole evening had there been a trace of that strange, warm feeling of last night when, just before we went home, we had gone outside and down to the water’s edge behind Pete’s. The lake was rough and the waves tossed up, white with spray, sucking at the shore, and the wind went soughing through the line of old willows, swaying them with a sonorous, restless rhythm. We stood quiet, listening to the night sounds and watching the pale moon, half hidden by the gray cotton cloud stretched across it. Inside, Pete’s had been so full of music and laughing but out here the whole stretch of dark water and the thick weeds and the swaying trees on the shore seemed tormented by a strange, aching lonesomeness, and the wind blew in cool and damp from the lake with the familiar, moist smell of fish. Out here something in me relaxed; all the awkward restraint that had haunted me through the evening was lifted and I felt like taking off my shoes and dancing in the grass.

As we were going back to our car I noticed all the silent, dark cars parked around the gravel lot and remarked to Jack, “There don’t seem to be nearly as many people inside as there are cars parked out here.”

He looked at me a moment, as if he thought I was joking, and then said with an odd laugh and an inflection which I didn’t quite understand, “You’re a good kid, Angie.” That’s all he said and it may have been just my imagination mingled with the mysterious spell of the lake but for a moment, for the only time during the whole evening I thought he looked at me as he had last night.

But the feeling couldn’t last wh

en, during that short ride back to town, I realized again with doubled humiliation what a terrible date I’d been. Jack didn’t look at me once all the way home, or try to talk and as soon as we got in front of my house he jumped out of the car and came round to open my door. It seemed so funny, walking up the sidewalk, that just this time the night before I had been doing the same thing and wondering if he would call me again; and now he had called and I had gone out with him and here I was, still wondering if there would be another time. But tonight it was tinged with a little hopelessness. After the way I had acted what would any boy do?

Standing on the front steps, I had an uncomfortable feeling that there was something I should say; yet a girl just can’t blurt out an apology for not being like other girls! I could almost feel the right words on my tongue, but when I opened my mouth to speak there was nothing there at all. I broke off a bit of the tall spruce that grows beside our steps and smelled the pungent piny odor rising in the air. Jack was standing running his finger round and round one of the scrolls in our wrought-iron stair railing. “Angie,” he said slowly, “Angie, I’m going to be out of town for a couple of days.” My heart slipped down a little. This was his way of saying that he wouldn’t see me for a couple of days—a couple of days that would probably merge into a week and then turn out to be the rest of the summer. “Going up to Green Bay,” he explained, “to see a cousin of mine and I won’t be back till Friday afternoon some time.” That’s all right, my mind said hurriedly. That’s all right, Jack. You don’t have to tell me anything. I know how I’ve acted tonight. “I wondered,” he went on, “if you’d like to go to the dance at the Country Club with me on Friday night. It’s the first one of the summer and I thought maybe you’d like to go!”

Lying in bed that night I thought it over. I had wanted an invitation to that dance more than anything else in the world, but now that I had been asked I hardly wanted to go because I could tell just what it would be like. My mother, who is always good about things like that, would buy me a new summer evening dress to wear; and my two older sisters, who would probably be going too, would arrange my hair and lend me perfume to dab behind my ears and on the hem of my dress so I would swish up a glamorous smell when I walked; and there would be Kitty, sitting on the edge of her bed in her pajamas, watching each step and saying over and over, “Oh, how nice you look!” When we were all dressed my mother would stand back to look at us with her eyes shining, thinking probably, how short a time ago it seemed since we were just little girls. Of course, I would smile and pretend to be excited and so glad to be going but all the time, inside, I’d keep remembering how it had been at Pete’s when I hadn’t been able to talk to the fellows at all and I would keep thinking of how I had watched the cross parrot, pretending to be very interested in his chipped beak and yellow eyes just because no one bothered to talk to me.

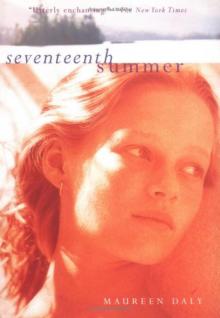

Seventeenth Summer

Seventeenth Summer